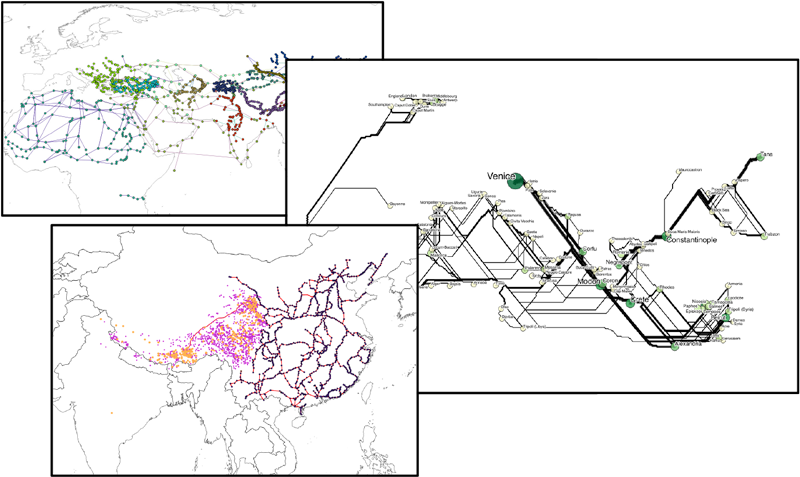

A small sampling of historical network datasets

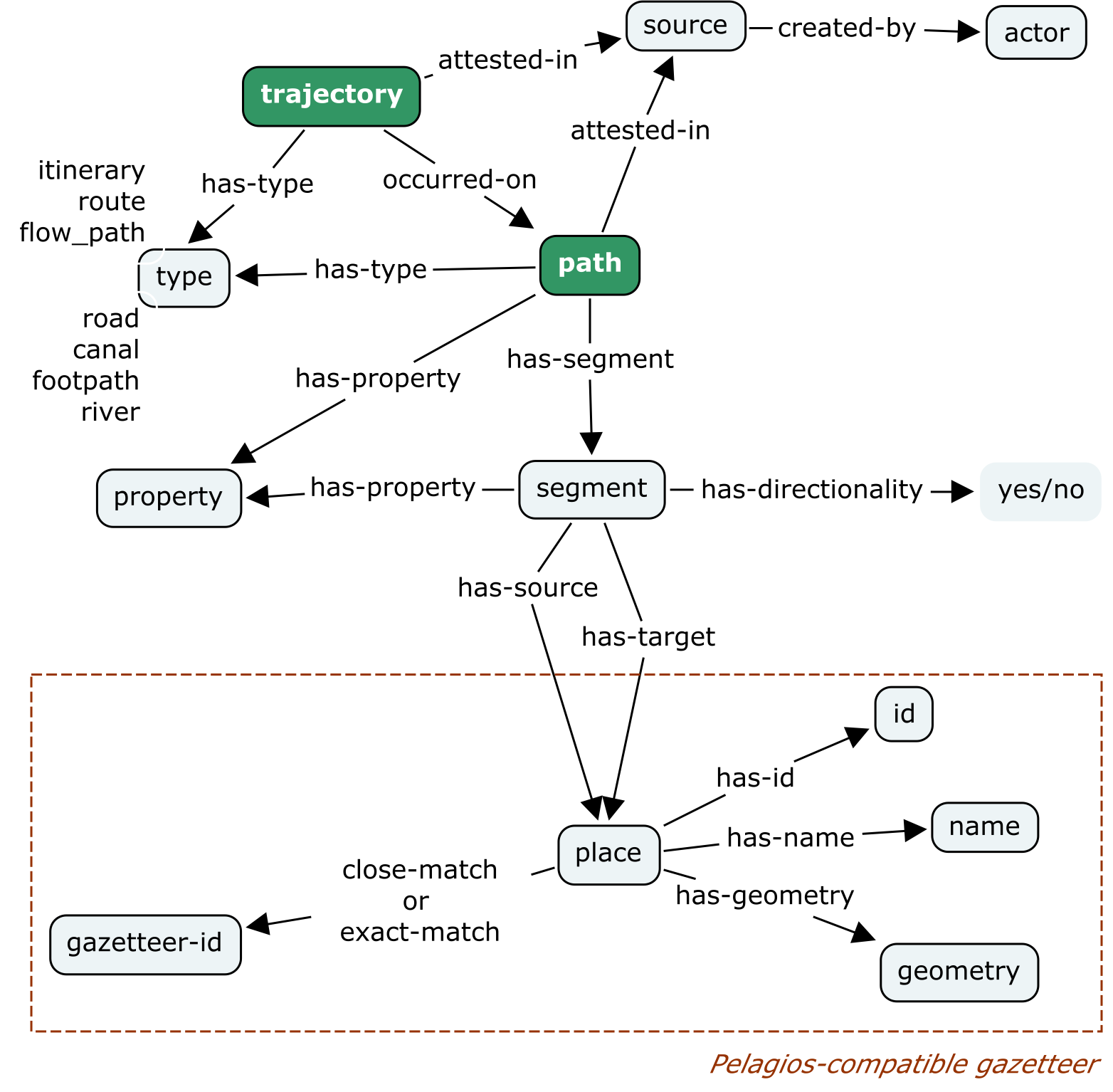

I believe there would be widespread interest in a global collaboratively developed system, organized similarly to Pelagios, aimed at creating and linking data records for attested historical trajectories (e.g. itineraries, routes, commercial flows, correspondence) and paths (roads, rivers, canals, sea currents). In this provisional semantics, a trajectory is evidence of some person(s) or thing(s) moving from here to there (then there, etc.), at a known, approximate or estimated time and/or in a particular sequence, as attested in some source. A path is the physical medium for trajectories.

Both paths and trajectories can be represented as two or more places and one or more segments (nodes and edges in network parlance). Place nodes are necessarily “geographically embedded” and typically represented by feature centroids. The geometry of paths between nodes for various types of trajectories may be known, estimated, or in the case of some flow data, of no concern.

Historical gazetteers in the Pelagios ecosystem represent only named places. Most are point-like features (e.g. settlements, sites); increasingly, polygonal features are included as well (e.g. regions, administrative areas). But what of historical movement—trajectories between named places along paths? The simple data models used for the Pelagios interchange format and for most gazetteers do not accommodate trajectories and paths.

Not surprisingly, the first early geographic document geo-parsed in Pelagios’ Recogito tool describes an itinerary: “Itinerarium Burdigalense: the Itinerarium Burdigalense (or Bordeaux Itinerary) […] a travel document that records a Pilgrim route between the cities of Bordeaux and Jerusalem.” Although we know each attested place was part of a traveled route, by virtue of its association with a text having “itinerarium” in its title, those relationships are not recorded formally in gazetteers, and therefore not readily discoverable and analyzable as routes and components of networks.

The Orbis Initiative

In February, 2015 I submitted a proposal to the National Science Foundation for a fairly large grant ($1.6m over 3 years) to develop the Orbis Initiative. Although reviews were quite positive, it was not funded. The project was designed to facilitate the creation, archiving, discovery, linking, and analysis of historical geospatial network data for “everywhere and every when.” The project name was borrowed from an interactive scholarly web application I helped build, originally published by Stanford University Libraries in 2012 and significantly upgraded in 2014, ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman Empire (hereafter, ORBIS: Rome).

Whereas ORBIS: Rome is an authored model of travel and transport for a particular region and period aimed at answering the research questions of one Classical scholar (Walter Scheidel), the Orbis Initiative is instead a system for creating, storing, and linking geospatial network data spanning potentially all places and periods—a distributed repository along with a set of relatively simple interactive web-based tools to facilitate its use. The design and proposed development of the Orbis Initiative is a response to researchers who have expressed a desire to build ORBIS: Rome-like applications for their own areas and periods of study. Importantly, the intent is not to expand the ORBIS: Rome network transport model, but to provide a generic data infrastructure and tools to facilitate development of other models and modeling approaches.

I remain convinced this would be a worthwhile undertaking and subsequently, two opportunities have emerged to begin some of the work described in the grant proposal, at a much smaller initial scale; I’ll discuss one of them here.

A Community of Interest?

Writing the Orbis Initiative grant entailed recruiting collaborators with varied exemplar datasets being developed for ongoing research. Several of those projects are concerned with processes of cultural diffusion and commercial activity—separately and in concert—in East and Central Asia and between Asia and Europe over extended periods. Their aggregated temporal extent is 7th century BCE to 16th century AD. Researchers in those groups, and now a few others, have indicated an immediate pragmatic interest in exposing and linking their data for common benefit. Meetings to discuss next steps have begun.

Something Like Pelagios

An Orbis Initiative would replicate several aspects of the Pelagios Project, which has gained terrific momentum in developing online resources, methods and software for linking historical gazetteers. I believe Pelagios’ success is due in large part to its “ground-up” nature—the fact it answers some immediate requirements of a distinct community of interest for the Classical Mediterranean. Its spatial and temporal extents and software tool development scope are growing organically, expanding upon smallish proofs-of-concept that people find useful. Tools developed so far facilitate data creation (Recogito) and data discovery (Peripleo). The Pelagios approach offers a stark contrast with some “build it and they will come” data repository projects attempted in recent years.

In the same vein, a pragmatic start to an Orbis Initiative could be seeded by meeting the requirements of the above-mentioned community of interest to link (and in a sense gather) their historical geospatial network data: connections by road, river, canal, and sea route between the places attested in Pelagios-compatible gazetteers.

A Conceptual Model

So, networks of trajectories are different in kind from place locations as commonly understood, and as such require a different, somewhat more elaborate data model. Furthermore, while all spatial data may include temporal attributes, some network data—itineraries for example—are inherently temporal; in fact they are events. Flows are essentially aggregated movement events.

In my experience a helpful first step in data modeling is to create a conceptual model of the entities and relations of what is being represented—an ontology design pattern if you will. Typically a collaborative undertaking, the resulting visualization provides a basis for the data schemas to follow, be they relational or graph. I’ve taken a first stab at such a model, using a recently published trajectory pattern (Hu, et al 2013) as a point of departure; input is invited and essential.

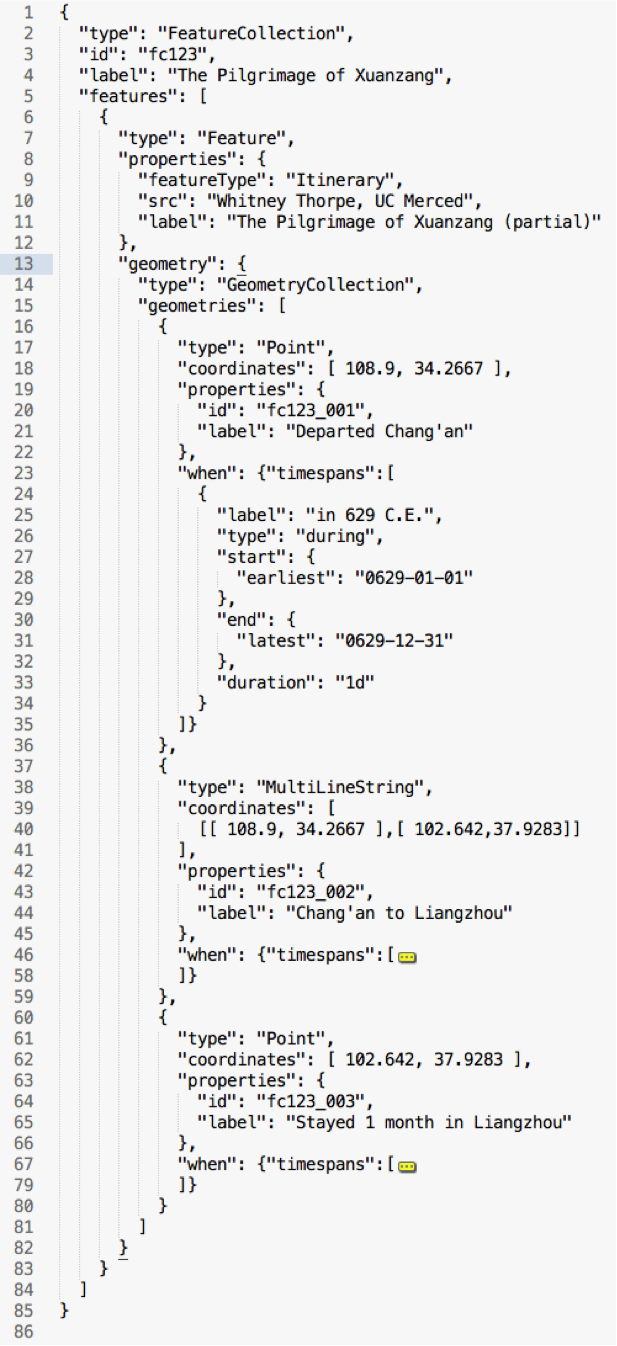

Data Format

The GeoJSON data format is in common use and provides a good starting point for a standardized representation of trajectories and paths. Granting that much data is initially gathered in spreadsheets, by and large if it is to be mapped or analyzed spatially, it makes its way into human-readable GeoJSON or the binary shapefile. GeoJSON represents geographic Features in a FeatureCollection, and spatial attributes are represented in a required Geometry object, but time is not accounted for natively. Although temporal attributes of a Feature can be recorded as one or more of a Feature’s Properties there is no norm or best practice for this and mapping software that consumes GeoJSON does not typically look for or make use of temporal attributes.

This can potentially be remedied by an extension to GeoJSON, such as the Topotime format I’ve been developing. Topotime data is valid GeoJSON, but it includes a new, optional When object, and leverages the sparingly used GeometryCollection object that is found in the GeoJSON specification.

One of my tasks at hand—which I welcome collaborative input on—is testing the efficacy of the Topotime model for the several types of historical geospatial network data found in the wild.

The Basics of Topotime

Topotime was initially conceived as a means for representing historical temporal data that is vague and otherwise uncertain, for visualization in browser timeline software and for the analysis of probabilistic relationships between and amongst events and periods.

The goals of the Topotime project have recently both broadened and simplified considerably—now essentially aimed at extending the GeoJSON format to account for time (including some of the difficult historical cases), without breaking GeoJSON. That is, Topotime data would be recognized as GeoJSON by any software that supports GeoJSON.

Work-in-progress is described, with a few toy examples, at https://github.com/kgeographer/topotime. I’m planning to work through varied and more complex data examples soon, then write some basic software that accesses Topotime’s unique attributes.

The following is a snippet to give a sense of it:

Next Steps

This effort does not have institutional support at this time, but if enough people feel it’s worth pursuing, we should seek it.

As mentioned earlier, a small group representing several active research projects focused on Asian maritime and land routes will be meeting soon to assess whether Topotime or something like it is appropriate for a “Pelagios for Networks.” We will make our results public for discussion, possibly through the Pelagios SIG infrastructure. More later… and comments are welcome.