When I began the Geographic Lens on Stories (GLOS) project, I imagined building a global atlas of creation myths as a way to map how different cultures have conceived the origins of the world, both conceptually and geographically. I hoped that by using modern NLP tools and embeddings, I could visualize conceptual relationships among myths: a geography of meaning.

The TL;DR: the work hit an epistemological roadblock. Its methods could only reveal the interpretive processes of LLMs and not the conceptual content of the myths themselves in any empirical sense.

Phase One

I spent months digitizing and normalizing 69 myths from Barbara Sproul’s Primal Myths, designing schemas, segmenting texts, and creating embeddings using Anthropic and OpenAI APIs. The work proceeded in phases, beginning with a 20-myth sampling.

The initial schema divided each myth across high-level dimensions: Primordial State (incl. entities present), Creation Sequence (events, incl. participants and locale), Cosmic Structure (incl. social and ecological hierarchies, dualities), and Distinctive Elements (free text). Each myth was submitted to an LLM with an elaborate prompt that requested values (or nulls) for each attribute. Significant manual normalization was required, as the models often described the same concept with divergent terminology.

I then generated whole-myth and section-level embeddings from these extracted values and performed clustering analyses to explore patterns of similarity across cultures and regions. The early results were promising, but the schema itself had been derived from LLM responses and my own non-expert judgment. It lacked grounding in any shared motivating theory and quickly became unwieldy.

Phase Two

In the second phase I added 49 additional myths from around the world and anchored a new schema in a respected work on comparative mythology, The Truth of Myth (Thompson & Schrempp). They propose “points to consider” for new students of mythology along five axes: time, space, quantity, quality, relation. My prompts followed these axes closely, requesting a mixture of free-text and standardized responses.

For example, the space axis asked for narrative location, landscape type, place correspondence, spatial symbolism, and spatial boundaries — all in free text.

Preliminary results suggested that this organization could inform a new “Schema_v2.” But eventually the realization came to me that every attribute in both schemas was again the result of a large language model’s interpretation. I wasn’t extracting meaning; I was eliciting it.

At that point it became clear that what I was analyzing was not the myths themselves, but the hermeneutic machinery of the model.

From Extraction to Interpretation

That realization changed the direction of the project. GLOS became less a study of world mythology and more a study of machine hermeneutics — how an AI trained on vast textual corpora constructs (or invents) meaning when asked to interpret a myth.

I shifted to asking broader, less constrained questions, along four dimensions: Central Metaphors and Oppositions, Cultural Lessons or Functions, Distinctive Features, and Brief Interpretive Commentary. Anthropic’s model Claude summarized the pattern succinctly:

“The model’s interpretive tone emerged clearly. Its commentary style was fluent and persuasive, yet strangely generic: every myth seemed to be about chaos giving way to order, the joining of opposites, the restoration of balance. It had learned the language of comparative mythology and was applying it reflexively. In essence, it was channeling the Lévi-Straussian worldview back at me.”

After reading some Lévi-Strauss, I agreed.

Embeddings as a Mirror of Interpretation

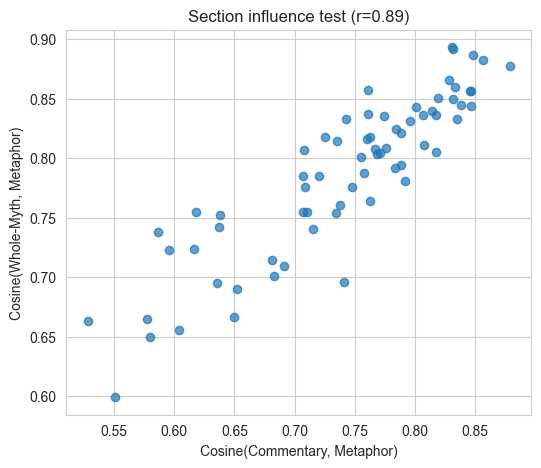

I continued the embedding analysis to see what the geometry of those interpretations might reveal. Each myth now had four section embeddings plus a whole-myth vector. Comparing them showed a clear pattern:

- Metaphors and Commentary were the closest pair in embedding space.

- The Metaphors → whole-myth similarity was nearly as strong.

A scatterplot across all myths produced a correlation of 0.89 between Commentary–Metaphor similarity and Whole-Myth–Metaphor similarity. Astonishingly high — and deeply telling. It showed that the model’s overall conception of a myth is dominated by its perception of oppositional structure. It was quantitative confirmation of what Lévi-Strauss proposed qualitatively: mythic meaning is organized through oppositions.

Mapping the Model’s World

In the final stage, I turned that insight outward and mapped these embedding similarities across regions. The 69×69 similarity matrices and regional heatmaps showed where the model perceived conceptual proximity — first in commentary (interpretive tone), then in metaphor (conceptual structure).

The results were both revealing and humbling.

In the commentary heatmap, global similarity hovered around 0.6–0.7 across nearly all regions — evidence of how homogenized the model’s interpretive voice is.

In the metaphor map, more structure appeared: China, Japan, and Australia formed tight internal clusters, while Siberia (and again Australia) showed lower similarity to other regions. Whether this reflects genuinely distinctive mythic styles or simply uneven model familiarity is impossible to know.

In truth, these maps visualize the model’s own geography of interpretive coherence — its zones of certainty and its blind spots — not the world’s mythological landscape.

What Remains

So what has GLOS accomplished? Not the empirical discovery I had once imagined, but something subtler: a demonstration that large language models had spontaneously reproduced the structuralist insight that oppositions organize mythic thought. They do this not because they understand the myths, but because they have internalized the linguistic and conceptual patterns through which humans have described them.

The work has also produced a reusable framework for structuring interpretive text into analyzable semantic layers — and that may prove useful in future collaborations with scholars in folklore or comparative mythology.

But ultimately, this experiment turned the lens back on me and because I don't possess sufficient expertise in comparative mythology to evaluate the models' interpretations, the GLOS project is suspended unless and until I find a better approach to realizing its goal.

Closing the Circle

One of my earliest GLOS posts was co-authored with ChatGPT, acknowledging from the outset that this was a collaborative experiment in meaning-making. It feels appropriate that this concluding reflection should also be co-written.

I began with the hope of charting a geography of creation myths.

I end with a geography of how a machine thinks about creation myths.

Perhaps that is still a kind of map — a topography not of the world’s stories, but of the interpretive imagination that both humans and machines now share.