ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World

Screenshots (2012 version)

Organization

Stanford University Libraries; Department of History

Roles

Interface designer; front-end developer; systems integrator; geospatial consultant

Technologies

PHP; JavaScript web mapping; PostgreSQL/PostGIS; spatial network modeling; HTML/CSS; Apache/LAMP deployment; server scaling and caching

Description

ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World is a computational model of travel, transport, and communication across the Roman Empire. Conceived by historian Walter Scheidel and implemented as a sophisticated cost-based network model by Elijah Meeks and several graduate student collaborators, ORBIS reconstructs movement along roads, rivers, and maritime routes in varying seasons and travel modes. Since its release, it has become one of the most widely recognized digital humanities projects and a touchstone in historical GIS.

When I arrived at Stanford Libraries in 2012 as the institution’s second digital humanities research developer, my first assignment was to build the initial public-facing interface for ORBIS. Elijah had created a powerful desktop-based model using SQL, PHP (as middleware), and an elaborate geospatial dataset of Roman transport infrastructure, but there was no usable interface through which scholars or the public could explore the system. My task was to translate this model into a functional, intuitive web application.

To do this, I immersed myself in the underlying network model: the cost functions, the hydrological and road networks, the sea mesh, and the SQL queries that produced travel-time and travel-cost calculations. I co-designed then implemented the web interface that allowed users to select origin and destination points, adjust travel parameters, and visualize resulting routes and costs on a map. I also managed deployment and stabilization during the project’s explosive public debut. ORBIS received extensive international press attention, and the infrastructure required rapid scaling and optimization—another aspect of the work I handled.

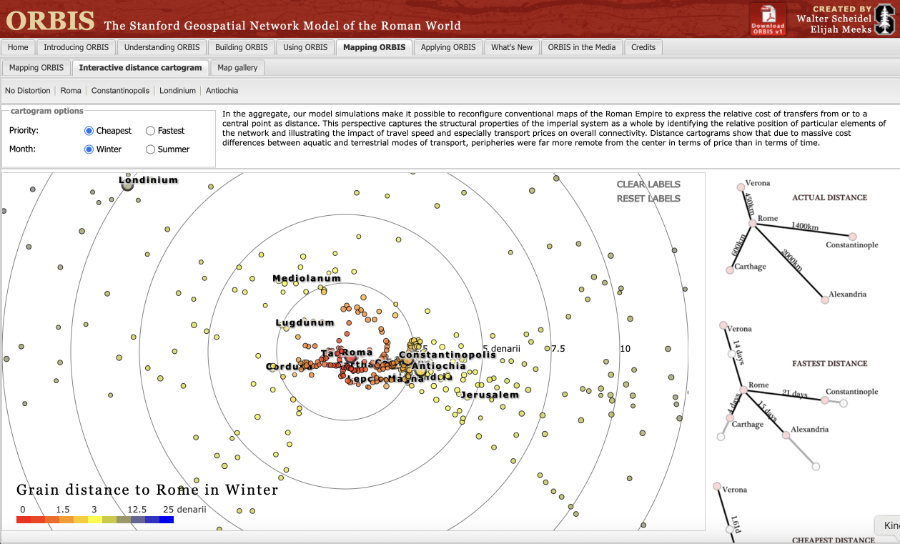

Some time later, Elijah rebuilt the ORBIS interface with the D3 JavaScript library, adding a suite of innovative visualizations (including travel-cost cartograms) and significantly extending the project’s expressive range. That version—beautiful, influential, and the one most people know today—superseded my interface, while relying on the same core model and infrastructure. My contribution was the creation of the first public ORBIS interface and the launch that introduced the project to global audiences.

In the course of developing the public interface, Elijah and I recognized that ORBIS was not simply a tool but a new kind of scholarly expression, that we came to call an interactive scholarly work. The model embodied argument, interpretation, methodological transparency, and critical framing in ways impossible to convey in print alone. To support this, I advocated for the inclusion of extensive contextual essays on the site, articulating Scheidel’s goals, the historiographic premises of the model, and the interpretive limits of its results. Scheidel responded by writing a set of framing essays that now serve as an intellectual anchor of ORBIS. This articulation of an interactive scholarly work genre later informed Stanford Libraries’ broader turn toward supporting interactive scholarly publications, a shift that shaped the direction of digital humanities development at the university in the years that followed.

ORBIS and the Vision of “ORBIS in a Box”

Following ORBIS’s success, Walter Scheidel convened an international symposium of Roman historians to respond to the model. I attended as an observer, and one message emerged repeatedly: scholars wanted to build ORBIS-like systems for other regions and historical periods. They imagined a generalized, reusable framework for historical network modeling.

Neither Scheidel nor Meeks wished to pursue such a platform. They had invested more than a year of intense work and viewed the ORBIS project as complete. They also believed others could adapt the existing code. But the codebase (both Elijah’s backend and my early frontend) was too complex and idiosyncratic to serve as a template.

The insight that digital humanities projects would increasingly need to produce reusable infrastructure stayed with me. When requests arrived from elsewhere for ORBIS-like tools, Scheidel and Meeks referred many of them to me. I became the informal steward of a concept ELijah had christened “ORBIS in a Box,” a generalizable framework for historical transport modeling.

I presented the idea at a symposium on historical sea commerce in Paris and later participated in a hackathon in Vienna organized by the developers of the CIDR and the criteria for the kinds of DH work Stanford Libraries would sponsor.

ORBIS thus occupies a meaningful place not only in the field of spatial history but also in my own development as a builder of DH infrastructure: it was where I first encountered the community’s need for generalizable tools and began to pursue that line of thinking in earnest.